Project

In the late spring of 1922, during the reclamation works of the Po delta lagoons (locally called valleys) nearby Comacchio (Ferrara), the first burials of the Etruscan city of Spina unexpectedly came to light. These sites had been searched for in vain for a long time by erudites and scholars. Spina had been remembered by ancient authors for the relationships it had with the great Athens of the 5th century BC and with the sanctuary of Delphi, the place of maximum self-representation of the Greek world. Thanks to reclamation, the once considered mythological city of the Adriatic became real.

On the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the discovery of the necropolises of Spina, the Ministry of Culture, through the Directorate-General for Museums, has set up a Committee to promote the anniversary celebrations, which will be divided into various scientific and educational initiatives, coordinated by the Directorate in collaboration with the territorial divisions of the MiC, i.e. the Regional Directorate of Emilia Romagna Museums and the Superintendence of Archeology, Fine Arts and Landscape for the metropolitan city of Bologna and for the provinces of Modena, Reggio Emilia and Ferrara, with local administrations, i.e. the Municipality of Comacchio, the Municipality of Ferrara and the Emilia Romagna Region, and the national and international universities that have been carrying out, for years, research and excavations on the ancient settlement: the University of Bologna, the University of Ferrara and the University of Zurich.

Distributed throughout the year and throughout the country, the activities started with the exhibition “Spina 100: from myth to discovery”, inaugurated on 1 June 2022 at the Palazzo Bellini in Comacchio.

In mid-December, at the National Archaeological Museum of Ferrara, the exhibition “ Spina etrusca. A great port of the Mediterranean ” will be launched, which will move in 2023 to Rome, at the National Etruscan Museum of Villa Giulia.

In the meantime, a rich program of meetings and conferences, dedicated to the history and archeology of Spina, is scheduled both in Comacchio and in Ferrara, with significant appointments also outside the regional territory.

The set of projects aims to tell the relevance of archaeological discovery in its many faucets, from the history of the discipline to the importance of the archaeological and material heritage brought to light in these hundred years of research, from the phenomena of dispersion of contexts in multiple museums. of the world to the radical and continuous transformations of the lagoon landscape, focusing, in particular, on the settlement of Spina as a fundamental place of connectivity in the Mediterranean.

Etruscan Spina: The ancient context and the current places

Literary sources and mythological tales reveal how, for the Greeks, Spina should have represented the welcoming delta of a fabulous river, point of entry into the Po valley and towards the lands beyond the Alps, the bridgehead of Etruscan power in the Adriatic and the gateway to entrance of Greece into the West. It served to locate the myth of Phaeton and his sisters, but also that of Icarus and Daedalus, as well as many of the exploits of Heracles.

The studies on materials, started after the first discoveries, gradually traced the historical story of Spina and the consistency of its trade (from the end of the 6th to the 3rd century BC), while the excavations and researches of the last decades have, in general terms, led to the distinction of the physical spaces and the peculiar characteristics of the site.

The place that the founders chose to establish the city of Spina, around 530/20 BC, was a lagoon landscape, barred towards the sea by coastal strips, in which the most ancient houses were raised up using mainly wood and thus protected against water. The site of the inhabited area, identified in the 1960s and also investigated in recent years, is in fact located on the edge of the ridge of the ancient Po branch called Spinete, in a constantly evolving environment.

Within a few decades from its foundation, the housing system had to evolve towards a reclamation settlement, bordered by canals and characterised by piling and bridging. In the phase of maximum expansion of the city, between the entire 5th and 4th centuries BC, the housing structures, sometimes resting on large square poles, appear to have been totally built in a sub-aerial environment.

This is how the characteristics of a settlement are outlined, with an extension of about 6 hectares, chosen and designed for maximum accessibility, favored by the natural course of the Spinete river towards the east and strengthened by the imposing hydraulic work of an artificial canal to the west. The urban scheme is therefore characterized by regular blocks, marked in the center by the large artificial watercourse, and minor canals orthogonal to it.

The picture is consistent with the identification of a port center, with houses, warehouses and production plants capable of receiving goods and storing them pending their redistribution through the territory or their transfer onto Athenian ships, in a context that clearly highlights the constant concern to reclaim the land contested by water.

Whoever tries today to see a foothold for literary accounts in that slight elongated hump of short width, identified as one of the parts of the town of Spina, probably feels a sense of estrangement: the artificial canal has disappeared, the riverbed of the Spinete that lapped the city and the coastline that the Spineti would have glimpsed from afar, looking at the bumps of their necropolis, is unreachable.

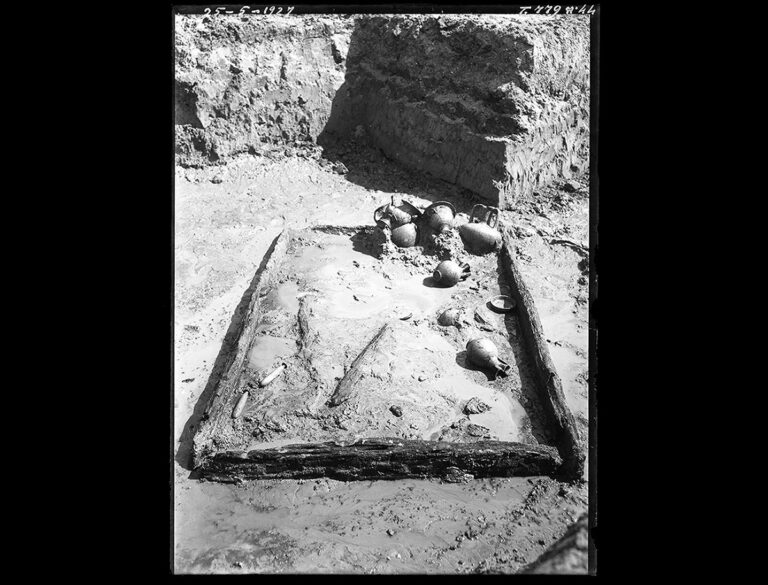

Precisely on those sandy mounds, which constituted the most prominent part of the coastal barriers in front of the city, coinciding with the micro-relief of the ancient delta landscape of the Etruscan era, the Spineti found shelter for their dead from the beginning of the 5th to the end of the 3rd century B.C The tombs of Valle Trebba to the north and those of Valle Pega to the south in fact constitute a single large burial ground of over four thousand burials, where the Spineti buried their dead for about ten generations.

The wooden coffin was very frequently present, destined to accommodate both the buried and cremated, accompanied by grave goods that for the most part, especially in the most ancient period, consist of vases for the consumption of wine, in an almost constant reference to the ideology of the banquet in the Afterlife.

The discovery of numerous tomb markers, more often made up of simple cobbles, highlights the desire to make the burial explicit on the outside. The most recent studies, focused on the dynamics of occupation of spaces over time, on the identification of distinctive signs both outside the tomb and in the selection of the objects of the grave goods, aim to give the burial ground also in terms of social hierarchies and groupings of family members.

Trade must have constituted the main occupation and the greatest source of wealth of this city, a place where the activities of Greeks and Etruscans coexisted with mutual interest. The commercial movement in Spina is defined above all thanks to the extraordinary variety and quantity of its markers, which, however, were to be only a small part of the trade consisting mainly of perishable goods. The thousands of imported artefacts returned from the necropolis but also from the inhabited area, which are well characterized alongside local productions. The prevalence of Attic products appears in the funerary objects of the 5th century BC, but also from the beginning of the 4th, so much so that the city can be rightly considered, to use a definition of Beazley ” the largest single source of Athenian pottery in the Greek or Greek world “. It is a flow that, without solution of continuity, begins around 530/20 BC, as evidenced by the oldest testimonies from the town, has a peak of maximum expansion around the central decades of the 5th century, to then run out before the last decades of the 4th.

All the materials coming from the ancient Spina, both the extraordinary grave goods of the necropolis and the finds of the inhabited area, are now preserved in two different museums, the historic National Archaeological Museum of Ferrara, inaugurated in 1935 and expressly created to house the evidence of the ancient city, and the recently established Delta Antico di Comacchio Civic Museum, in which the testimonies of Spina are composed alongside the documents of the entire history of the delta territory.

Archaeological site Open Air

The inhabited area of the Etruscan city, identified in the Mezzano Valley, in the Municipality of Ostellato, has been the subject of numerous excavations over the years, immediately covered for conservation issues.

In order to experimentally reconstruct a part of this inhabited area, otherwise “invisible”, in June 2022 the “open air archaeological museum” was inaugurated where, with the methodologies of experimental archeology and starting from the excavation data, a section of the Etruscan settlement, perfectly inserted in a place of extraordinary beauty, such as that of the Comacchio Valleys, still very similar to the environment in the which arose the ancient Etruscan city.